Free ABSITE Sample Questions

See why TrueLearn is a trusted resource for thousands of medical students and residents. We understand that it’s all about the content. That’s why we have high-yield ABSITE practice questions written and screened by high-performing physician authors, which are updated on a regular basis to ensure our SmartBanks stay up-to-date with exam blueprint changes.

Below are free ABSITE sample questions so you can see what we mean, with the first one being from our 2026 New Edition.

Try This ABSITE Sample Question from the 2026 New Edition

A 35-year-old healthy woman presents with a 6-week history of dysphagia. An esophagogram is shown below. Which of the following is the most definitive treatment for this patient?

- A) calcium channel blockers

- B) Botox injection

- C) pneumatic dilation

- D) Heller esophagomyotomy with Dor fundoplication

- E) Heller esophagomyotomy with Nissen fundoplication

The Answer and Explanation

Did you get it right? The correct answer is D, Heller esophagomyotomy with Dor fundoplication.

This patient has an esophagogram with the classic finding of a “bird-beak” appearance, suggesting achalasia.

Due to the high long-term success rate of operative management, surgery should be considered as first-line therapy for good operative risk candidates, especially in young patients less than 40 years old. Operative management consists of distal (Heller) esophagomyotomy through both the longitudinal and circular muscle layers.

This procedure can be performed laparoscopically in most instances. The addition of a partial fundoplication, such as a Dor or Toupet, helps to prevent postoperative reflux symptoms. It is important to note that a complete (Nissen) fundoplication is contraindicated in patients with an esophageal motility disorder such as achalasia, and only a partial wrap should be performed. Esophagectomy is rarely performed in achalasia but may be indicated in cases of end-stage disease with a tortuous (megaesophagus) or sigmoid esophagus.

Per-oral endoscopic myotomy (POEMS) is a novel approach by which the myotomy is performed endoscopically via a submucosal tunnel. It is currently unknown if the long-term results are comparable to Heller myotomy.

“Bird-beak” appearance (red arrow) due to dilated esophagus on barium swallow study.

Incorrect Answer Explanations

Answer A, calcium channel blockers: Medical treatment includes calcium channel blockers or nitrates to relax the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) and can provide symptom relief in the short-term. However, results are often limited by side effects, and patients have poor long-term outcomes on medical therapy alone, generally requiring definitive surgical management for symptom control.

Answer B, Botox injection: Botox injections into the LES often require repeated treatments as symptoms recur more than half of the time within 6 months. Botox is a good treatment choice for high-risk patients (for example, the elderly or comorbid), as it is the least invasive option.

Answer C, pneumatic dilation: Pneumatic dilation has comparably high success rates compared with myotomy; however, patients frequently require repeated interventions.

Answer E, Heller esophagomyotomy with Nissen fundoplication: Although a Heller myotomy is the first-line therapy for good operative risk candidates, a Nissen (360-degree) fundoplication is contraindicated due to the patient’s esophageal dysmotility. A partial wrap, such as a Dor or Toupet, should be performed instead.

Bottom Line

Esophagomyotomy should be considered as first-line therapy for good operative risk candidates with achalasia, especially in young patients less than 40 years old. A partial (not complete) wrap such as a Dor or Toupet fundoplication is generally performed concurrently to reduce the rates of postoperative reflux.

Another Free ABSITE Practice Question

A 55-year-old man with a history of chronic pancreatitis presents for evaluation of surgical treatment options. MRCP demonstrates a large inflammatory mass in the head of the pancreas with no evidence of distal ductal dilatation. Endoscopic ultrasonography with fine-needle aspiration does not demonstrate any evidence of malignancy. Which of the following procedures is correctly matched to its description and is the most appropriate treatment option?

- A) Puestow procedure; distal pancreatectomy

- B) Frey procedure; longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy

- C) Whipple procedure; distal pancreatectomy

- D) Bern procedure; coring out of the pancreatic head plus longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy with a Roux-en-Y pancreaticojejunostomy

- E) Beger procedure; resection of pancreatic head with a Roux-en-Y jejunal loop as side-to-end and side-to-side pancreaticojejunostomy

The Answer and Explanation

Did you get it right? The correct answer is E.

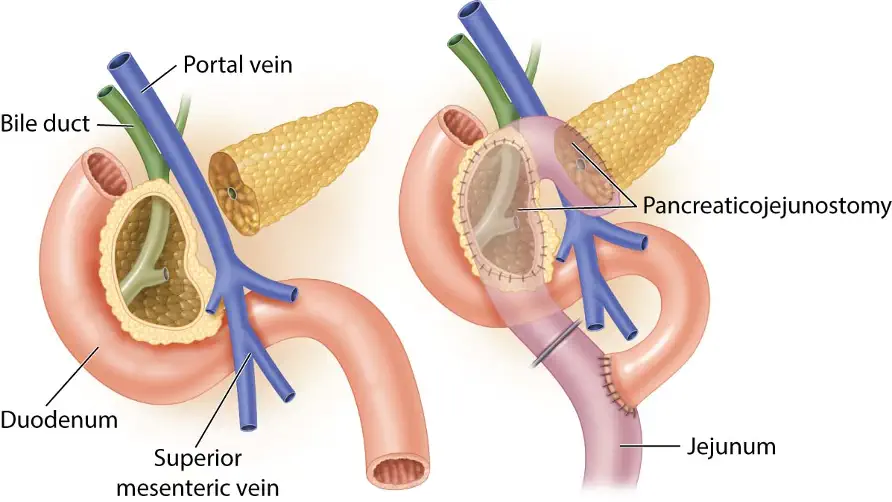

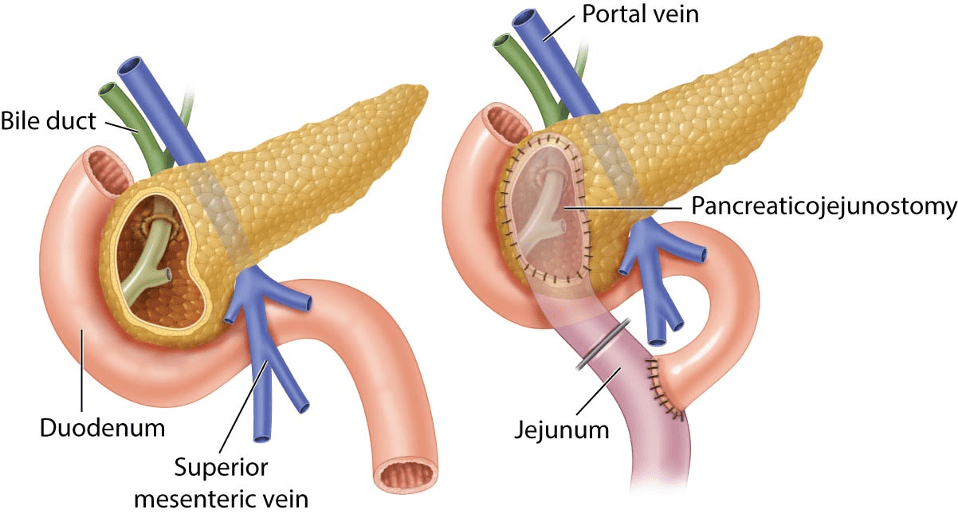

The Beger procedure is a duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection procedure. The pancreatic head is dissected to the level of the portal vein, and cored out, leaving behind a thin rim of pancreatic tissue abutting the duodenum. This is then reconstructed with 2 anastomoses using a Roux-en-Y jejunal loop to the pancreatic tail remnant (end-to-side) and to the excavated pancreatic head (side-to-side). This is typically reserved for patients with a large inflammatory mass in the head of the pancreas with no evidence of distal ductal dilatation. The lack of distal ductal dilatation is key in selecting the Beger procedure over other surgical approaches, as this makes the end-to-side pancreaticojejunostomy the most appropriate anastomosis.

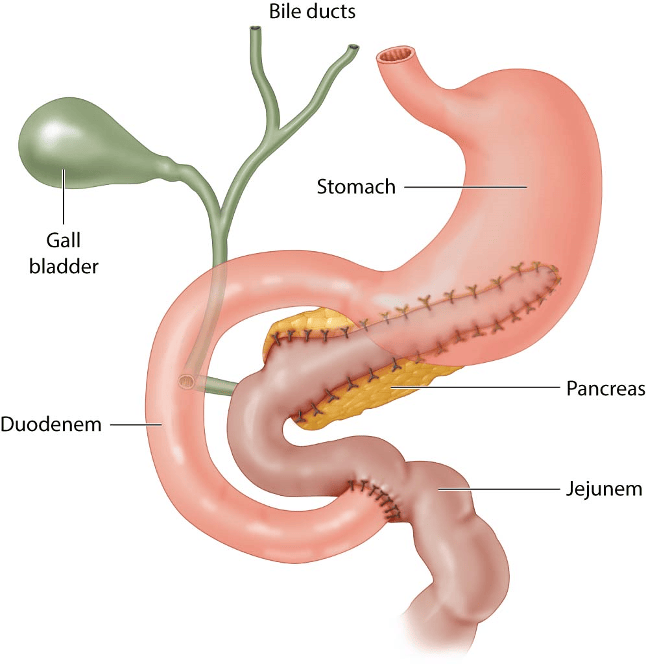

The diagram below illustrates a Beger procedure:

Incorrect Answer Explanations

Answer A: The Puestow procedure (illustrated below) is a longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy (not a distal pancreatectomy). This is typically reserved for chronic pancreatitis with dilatation of the pancreatic duct (≥ 7 mm). The Puestow procedure has an 80% rate of immediate pain relief, with about 60% of patients achieving long-term pain relief.

Answer B: The Frey procedure (illustrated below) involves coring out the head of the pancreas with a longitudinal dissection of the pancreatic duct toward the tail. The reconstruction is subsequently performed with a Roux-en-Y pancreaticojejunostomy. This is typically reserved for smaller inflammatory masses of the head of the pancreas and dilated pancreatic ducts. Again, the distal duct dilatation of ≥ 7 mm is key in the selection of any procedure that includes a longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy (ie, Puestow or Frey procedure).

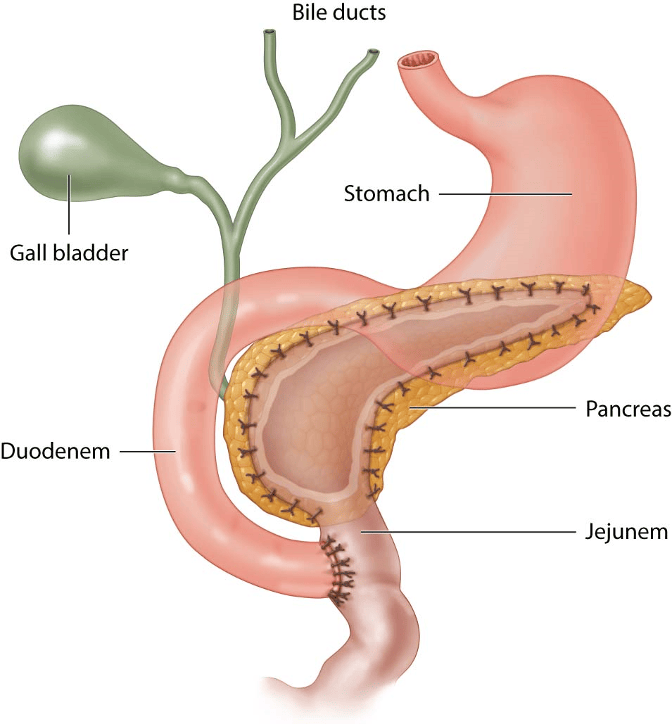

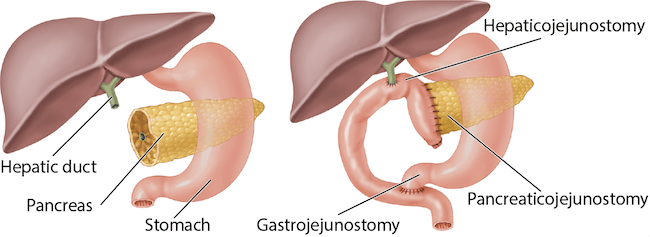

Answer C: The Whipple procedure, or pancreaticoduodenectomy (illustrated below), entails resection of the pancreatic head, duodenum, and distal one-third of the stomach. Reconstruction requires a gastrojejunostomy, pancreaticojejunostomy, and hepaticojejunostomy. The Whipple procedure is typically reserved for neoplasms of the head of the pancreas. In the setting of chronic pancreatitis, pancreaticoduodenectomy is rarely required unless malignancy cannot be excluded.

Answer D: The Bern procedure (illustrated below) is a modification of the Beger procedure that does not involve resection of the pancreatic head. In contrast to the Beger procedure, the pancreas is not transected at the level of the portal vein, which may be advantageous in the setting of extensive inflammation. Reconstruction only requires a single anastomosis with a Roux-en-Y jejunal loop to the pancreas. There is no significant difference in outcomes between the Beger and Bern procedures.

Bottom Line

The Beger procedure is a duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection procedure, which is reconstructed with 2 anastomoses using a Roux-en-Y jejunal loop to the pancreatic tail remnant (end-to-side) and to the excavated pancreatic head (side-to-side). This is typically reserved for patients with a large inflammatory mass in the head of the pancreas with no evidence of distal ductal dilatation.

TrueLearn Insight

The choice of surgical approach in a patient with chronic pancreatitis is largely dependent on 2 key factors: 1) distal ductal dilatation ≥ 7 mm. 2) pancreatic head involvement (ie, by mass or significant inflammation/fibrosis). Though it is more nuanced, one may simplify the selection process as follows:

- For dilated duct with head involvement – choose the Frey procedure

- For a normal or small duct with head involvement – choose the Beger or Bern procedures

- For a dilated duct without head involvement – choose the Puestow procedure

For more information, see:

Dudeja V, Christein JD, Jensen EH, and Vickers SM. Chapter 55: Exocrine Pancreas. In: Townsend C, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, eds. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery: The Biological Basis of Modern Surgical Practice. 20th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1520-1555.

Hartwig W, Koliogiannis D, Werner J. Chapter 58: Management of chronic pancreatitis: conservative, endoscopic, and surgical. In: Jarnagin WR, Allen PJ, Chapman WC, et al, eds. Blumgart’s Surgery of the Liver, Biliary Tract, and Pancreas. 6th ed. Elsevier; 2017:927-937.e3.

Strobel O, Büchler MW, Werner J. Surgical therapy of chronic pancreatitis: indications, techniques and results. Int J Surg. 2009;7(4):305-12.

Keep Taking ABSITE Practice Questions

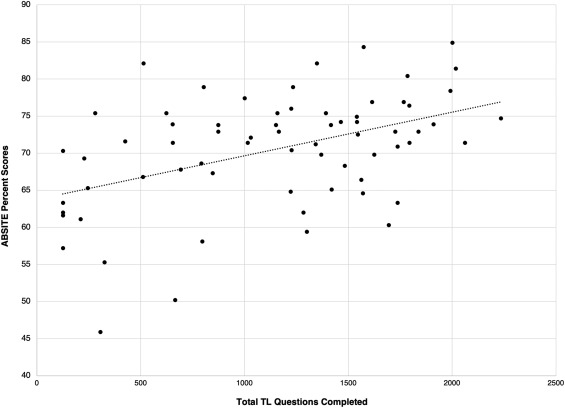

According to a recent study published by the Journal of Surgical Education, ABSITE scores are positively correlated to the number of TrueLearn ABSITE practice questions taken.

ABSITE exam success just got better! With updated questions, clear and concise explanations, and hundreds of visuals designed to support your exam excellence, TrueLearn’s ABSITE SmartBank is the top choice for the ABSITE.

Here’s what you get with the ABSITE SmartBank 2026 New Edition:

- 1000+ exam-style questions aligned to the ABSITE content outline

- Explanations that clearly and concisely break down why each answer choice is correct or incorrect

- 650+ surgical illustrations, decision-making algorithms, radiology images, and clinical photographs

- 480+ tables summarizing high-yield topics, conditions, and procedures

- Supported by references to authoritative textbooks, journal articles, and guidelines

- A test-taking interface that closely mirrors that of the actual ABSITE