The Importance of a Learner-Centered Approach in Healthcare Education—Understanding Metacognition, Self-Regulation, and Growth Mindset

Passive learning, which focuses on providing learners with information and expecting them to absorb it, is often the dominant approach in many educational settings. Classroom time typically involves the educator instructing while learners listen. The information is imparted in a one-size-fits-all format and every learner is expected to absorb the information in the same way.

In contrast, active learning is a learner-centered approach that involves learners in the process of learning, placing them at the heart of the educational activity. Rather than transmitting information to every learner through a single method or channel, this model of instruction engages learners with the content, one another, and the instructor.

While both passive and active learning have their advantages and place in the educational setting, active learning has been shown to support better long-term retention—crucial for building schema and establishing a strong foundational knowledge base—and create an environment where learners can engage in metacognition and self regulated learning while establishing a growth mindset.

Let’s dive into each of these theories—metacognition, self-regulation, and growth mindset—to learn strategies educators can deploy to create a learner-centered approach to healthcare education.

Metacognition

Psychologist James H Flavell coined the term metacognition to mean the knowledge we have of our own cognitive processes and our ability to control and reflect upon them.1 It is often defined as “thinking about thinking” or more specifically, how you think through a problem or situation and the strategies you adopt to overcome it. Metacognition involves self-reflection to plan, monitor, and evaluate2 one’s strengths and weaknesses, performance, success, and failure. When learners develop a keen awareness of how they learn—and not just what they learn—they can adapt their behavior to optimize learning.3

Research suggests that as learners’ metacognitive abilities increase, it helps them better focus on what they need to learn and this can lead to improved learning outcomes.4 Metacognitive study strategies have been identified as the single most important determinant of school learning5 and among the most effective behaviors for enhancing knowledge retention and learner understanding.6

The good news is, metacognition is a teachable skill and there are many ways to incorporate it into the classroom.7,8 This includes utilizing active learning tools like audio-visual mnemonics that encode and store information into memory, taking practice questions that force retrieval of knowledge, reflection assignments that encourage learning from past experiences, thinking out loud to model problem-solving processes, elaborative questioning to encourage deeper thinking, and scaffolding.

By employing metacognition pedagogy in the classroom and clinical settings, healthcare preceptors can help learners sharpen their critical thinking and problem-solving skills. This not only elevates learning outcomes but also empowers learners to become better clinicians—becoming more alert to their thought processes and resulting actions can help reduce errors in clinical settings.9

Self-Regulation

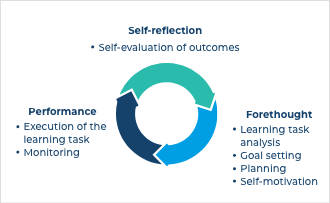

The ability to understand and control one’s learning—including goal setting, monitoring, instruction, and reinforcement—is known as self-regulated learning (SRL)9. Learners who use SRL actively drive and participate in their own learning process and continuously monitor their progress toward meeting specific goals. It’s a cyclical process: the learner plans the learning, self-monitors their performance, and reflects on the outcome.

They do this repeatedly, adjusting as they go along to suit individual and learning needs,10 and draw upon these skills:

| Cognition | Encode, memorize, and recall information, plus think critically |

|---|---|

| Metacognition | Understand, reflect, and observe thought process |

| Motivation | Beliefs and attitudes that influence the use of cognition and Metacognition |

Metacognition

Far from being an innate skill, SRL is a learned behavior that can be taught. Educators can train their learners to develop SRL by modeling how to learn, shifting the focus away from just relaying content or problem-solving techniques. Researchers agree that educators play an important role in helping learners improve their SRL capabilities,11 and there are two ways they can achieve that in the classroom12: directly (through instruction of strategies) and indirectly (by constructing a supportive learning environment).

In direct instruction, educators show and explain the importance of a certain strategy, its usage and application, and the skills involved. In the indirect approach, educators must conceive of a learning environment that fulfills a set of criteria that includes learning activities that enable learners to cover content while acquiring knowledge about SRL; provide them with options for learning; tailor support and feedback to individual learners; implement self-assessment; conducive to positive beliefs about one’s self-learning and problem-solving.13

Research has shown that learners who practice SRL effectively enjoy a multitude of benefits including more academic success and better optimism about their future, which contributes to the forming of lifelong learning habits.12 SRL capabilities have also been linked to increased academic motivation, leading to enhanced learning capacity.14 SRL learners tend to demonstrate a high level of self-efficacy as they draw on metacognitive strategies to observe and steer the quality of their learning.15 The more a learner utilizes SRL techniques, the more they can deepen their learning and the more likely they are to succeed academically.

Growth Mindset

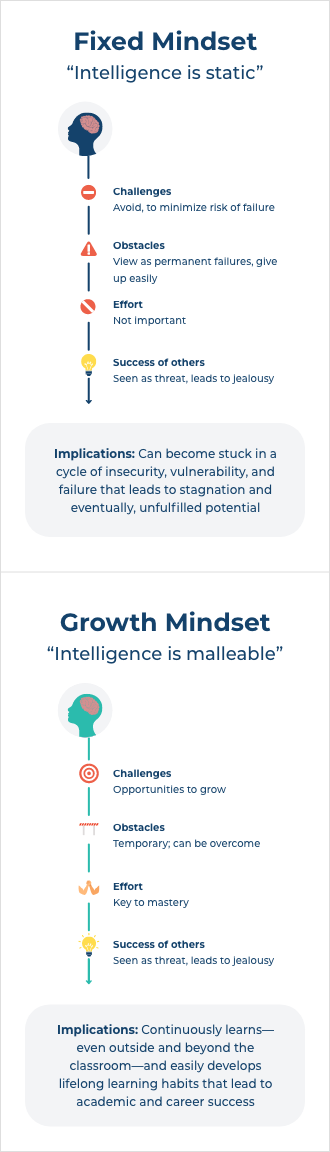

Is intelligence a fixed trait that one is born with or a changeable trait that can be improved? Learners’ belief determines whether they have a fixed or growth mindset16 and that will impact their learning performance and outcomes differently—a growth mindset has been linked to better academic achievements and higher college retention.17 That’s not surprising given that learners who embrace the growth mindset, perceive intelligence as an ability that can be enhanced through effort, help from others, and patience. They are driven by a keen desire to learn, embrace challenges as opportunities for growth, and are resilient in the face of setbacks.

Conversely, learners who have a fixed mindset and think that intelligence cannot be altered tend to view learning challenges as insurmountable tasks that they have low ability for, or that they simply are “not built for it”. They typically avoid challenges or give up when they face obstacles, ignore negative feedback, and pay little attention to effort.18

One important thing to note about a learner’s mindset is that it is not an innate belief but adapts to the situation and environment.19 Certain situations, events, or people, may trigger a fixed mindset whereas others promote a growth mindset. It is not uncommon for a learner to have a fixed mindset about one subject and a growth mindset about another. The learning environment is also an important factor that can shape mindsets. Similar to the indirect method of encouraging SRL, a classroom setting that is conducive and supportive of learning can influence the way learners perceive learning and their learning abilities. Educating learners about the changeable nature of intelligence increased their motivation to push through academic obstacles, leading to improvements in learning performance.20

The classroom context includes teaching practices: how the instructor approaches and communicates about learning and intelligence can influence learners’ behavior21—learners tend to mirror their instructors’ mindsets. Thus, the most effective way for educators to cultivate a growth mindset is to model it and these are the four behavioral signals22 that will communicate that to learners:

| Suggest that learners are capable of success | Mindset intervention |

|---|---|

| Describe success using action-driven terms or qualities like “perseverance” or “hard work” (versus “natural talent” or “gift”) inform learners that they too are capable of achieving the same. | Ask learners to list down their learning objectives, focusing on incremental and measurable goals that can be tracked to show growth. |

| Provide feedback and encourage practice | Mindset intervention |

|---|---|

| Create opportunities for practice and regularly provide feedback on their work to communicate to learners that there is always room to grow and progress. | Guide learners to reflect on their work, identify gaps if any, and plan ways to overcome the hurdles. |

| Support struggling and at-risk learners | Mindset intervention |

|---|---|

| How do you manage vulnerable learners? Supporting them with encouragement and motivation (versus showing frustration) shows that you consider setbacks as opportunities to learn, a core tenet of a growth mindset. | Acknowledge the efforts that learners have put in and spotlight any improvements or achievements they have made to remind them how they have progressed and that they can go further. |

| Value learning and development | Mindset intervention |

|---|---|

| When commenting on learners’ performance and growth, emphasize the learning and development process over capabilities. Put forth the idea that learning is a process that takes time and encourages learners to continue their efforts. | Phrases such as “Your thought process on this assignment was clear and succinct” will help in this pursuit, whereas something like “You appear to have a knack for this” implies that their performance was due to natural talent—and they may not have the same talent for another area of work, projecting a fixed mindset. |

By building these growth-signaling behaviors and actions into instructional strategies and learning activities, educators can create a growth mindset culture in the classroom and nurture the same mindset among their learners.

Centering On Learners

Strategies that facilitate metacognition, self-regulation, and a growth mindset should be utilized concurrently to create a learner-centered environment in healthcare education, as these theories are interlinked. For SRL to be effective, learners must also have the metacognitive awareness to interact with the learning process and track their own progress.23 Metacognition also factors in learners’ beliefs about learning; a growth mindset alone may not be sufficient to enhance learning engagement if they have not developed metacognitive abilities.4 Meanwhile, learners’ use of SRL strategies is driven by having a growth mindset.24

Embracing a learner-centered approach is impactful in high-stakes learning environments such as healthcare education, where lifelong learning habits are instrumental to success in academia and clinical practice. When healthcare learners and practitioners are able to ingrain metacognitive and SRL skills and growth mindset values, it will lead to optimal learning outcomes and in the long run, contribute to improved patient care and experience.

Activate a learner-centered approach to learning and drive success for your program by leveraging an e-learning solution built on cognitive science and powered by data analytics.

References

1 Flavell JH. Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive–developmental inquiry. Am Psychol. 1979;34(10):906-911. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.34.10.906

2 Zimmerman BJ, Moylan AR. Self-regulation: Where metacognition and motivation intersect. Handbook of metacognition in education. 2009;449:299-315. https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2010-06038-016.pdf

3 Price-Mitchell M. Metacognition: Nurturing self-awareness in the classroom. Edutopia. Published April 7, 2015. Accessed July 25, 2023. https://www.edutopia.org/blog/8-pathways-metacognition-in-classroom-marilyn-price-mitchell

4 Metcalfe J, Finn B. Evidence that judgments of learning are causally related to study choice. Psychon Bull Rev. 2008;15(1):174-179. doi:10.3758/pbr.15.1.174

5 Wang MC, Haertel GD, Walberg HJ. What influences learning? A content analysis of review literature. J Educ Res. 1990;84(1):30-43. doi:10.1080/00220671.1990.10885988

6 Pashler H, Bain PM, Bottge BA, et al. Organizing instruction and study to improve student learning: Institute of Education Sciences practice guide. Washington, DC: United States Department of Education; 2007.

7 Encouraging metacognition in the classroom. Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning. Published June 6, 2017. Accessed July 25, 2023. https://poorvucenter.yale.edu/teaching/teaching-resource-library/encouraging-metacognition-in-the-classroom

8 Medina MS, Castleberry AN, Persky AM. Strategies for improving learner metacognition in health professional education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(4):78. doi:10.5688/ajpe81478

9 TEAL center fact sheet no. 3: Self-regulated learning. LINCS | Adult Education and Literacy | U.S. Department of Education. Accessed July 26, 2023. https://lincs.ed.gov/state-resources/federal-initiatives/teal/guide/selfregulated

10 Zimmerman BJ. Investigating self-regulation and motivation: Historical background, methodological developments, and future prospects. Am Educ Res J. 2008;45(1):166-183. doi:10.3102/0002831207312909

11 Donker AS, de Boer H, Kostons D, Dignath van Ewijk CC, van der Werf MPC. Effectiveness of learning strategy instruction on academic performance: A meta-analysis. Educ Res Rev. 2014;11:1-26. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2013.11.002

12 Paris SG, Paris AH. Classroom applications of research on self-regulated learning. Educ Psychol. 2001;36(2):89-101. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep3602_4

13 Perry NE, VandeKamp KJO. Creating classroom contexts that support young children’s development of self-regulated learning. Int J Educ Res. 2000;33(7-8):821-843. doi:10.1016/s0883-0355(00)00052-5

14 Pintrich PR. A motivational science perspective on the role of student motivation in learning and teaching contexts. J Educ Psychol. 2003;95(4):667-686. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.95.4.667

15 Lavasani MG, Mirhosseini FS, Hejazi E, Davoodi M. The effect of self-regulation learning strategies training on the academic motivation and self-efficacy. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2011;29:627-632. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.285

16 Dweck, C. S. Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House; 2006.

17 Yeager DS, Hanselman P, Walton GM, et al. A national experiment reveals where a growth mindset improves achievement. Nature. 2019;573(7774):364-369. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1466-y

18 Egbert J, Roe M. Mindset theory – theoretical models for teaching and research. Wsu.edu. Accessed July 26, 2023. https://opentext.wsu.edu/theoreticalmodelsforteachingandresearch/chapter/mindset-theory/

19 Kapasi A, Pei J. Mindset theory and school psychology. Can J Sch Psychol. 2022;37(1):57-74. doi:10.1177/08295735211053961

20 Walton GM, Yeager DS. Seed and soil: Psychological affordances in contexts help to explain where wise interventions succeed or fail. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2020;29(3):219-226. doi:10.1177/0963721420904453

21 Park D, Gunderson EA, Tsukayama E, Levine SC, Beilock SL. Young children’s motivational frameworks and math achievement: Relation to teacher-reported instructional practices, but not teacher theory of intelligence. J Educ Psychol. 2016;108(3):300-313. doi:10.1037/edu0000064

22 Kroeper KM, Muenks K, Canning EA, Murphy MC. An exploratory study of the behaviors that communicate perceived instructor mindset beliefs in college STEM classrooms. Teach Teach Educ. 2022;114(103717):103717. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2022.103717

23 Wang MT, Zepeda CD, Qin X, Del Toro J, Binning KR. More than growth mindset: Individual and interactive links among socioeconomically disadvantaged adolescents’ ability mindsets, metacognitive skills, and math engagement. Child Dev. 2021;92(5). doi:10.1111/cdev.13560

24 Bai B, Wang J. The role of growth mindset, self-efficacy and intrinsic value in self-regulated learning and English language learning achievements. Lang Teach Res. 2023;27(1):207-228. doi:10.1177/1362168820933190

![How Educators Can Recognize and Help Students with Trauma [Webinar]](https://truelearn.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Educator-Webinar-How-Educators-Can-Recognize-and-Help-Students-with-Trauma.png)